Barks Blog

Bridging Training and Treatment: A Behaviorist’s Advice on Using Medications to Support Shelter Animals

By Kim Monteith

This article is based on an interview by the author with Dr. Karen van Haaften, a board-certified veterinary behaviorist with a focus on shelter behavioral medicine.

We ask animals to learn, adjust, and adapt in highly stressful environments. While behavioral interventions play a critical role in supporting animals with these changes, on their own they are not always enough for some animals. In many cases, bridging training and treatment can be the key. This is especially true when it comes to anxiety-reducing medications.

In a recent interview, Dr. Karen van Haaften, a veterinary behaviorist, shared her top insights and tips on how animal professionals can support animals prescribed or needing anxiety-reducing medication. These tips are valuable for helping animals in all environments, whether they’re in a shelter, at a rescue, or in a foster home. The goal isn’t to promote medication as a standalone solution—it’s to highlight how anxiety-reducing medications can support animal management, care, and behavior modification. Together, they help animals cope, learn, and move toward adoption.

Watch for Behavioral Changes—The Key to Understanding Animal Stress

Staff, volunteers, and trainers often spend the most time with animals in shelters, which means they are best placed to notice subtle (but important) behavioral shifts. As Dr. van Haaften explained, this might look like a usually social dog becoming withdrawn, or it could be a dog who starts pacing or vocalizing more frequently. These patterns can indicate increased anxiety or even a medical issue.

These subtle behavioral changes are not always obvious to the shelter medical team, who often don’t spend as much time directly with the animals. Recording and sharing detailed observations is key in helping to inform medical decisions, including whether a medication might be appropriate and whether it’s working or not. Staff, volunteers, and behavior teams are the biggest source of this information. Communication is key here. Medical teams need to get feedback on the patient’s response to medications, and the animal care teams need to know when new medications or doses are being trialed and potential side effects to watch out for.

When to Consider Anxiety-Reducing Medications

So, what prompts the decision to introduce medication? Dr. van Haaften outlined a few common scenarios where medication may be considered:

- To improve an animal’s welfare in the shelter, especially when the environment itself is a major stressor

- To reduce behaviors rooted in anxiety or fear, such as extreme reactivity, shutdown, or hypervigilance

- To support participation in b-mod (behavior modification) sessions when anxiety is otherwise too high

- To minimize distress during unavoidable stressors like a vet procedure, grooming, or a transfer

Dr. van Haaften shared the story of a highly fearful cat who couldn’t participate in training until meds helped reduce her anxiety. Once her excessive fear was controlled, the cat could finally start to engage and make progress with b-mod.

“Sometimes, a patient can’t even start to learn until we take the edge off their fear,” explained Dr. van Haaften.

How to Recognize Emotional Distress in Shelter Animals

Dr. van Haaften described two stress coping styles that are common in animals: active (barking, pacing, bouncing off the walls) and passive (hiding, freezing, shutdown). Both can indicate anxiety, and both are treatable with the right combination of b-mod and medication, if needed.

Other flags to look for include:

- Lack of progress with b-mod plans

- Physiological signs of stress (dilated pupils, trembling, panting, etc.)

- Noise sensitivity, hyper-reactivity, excessive startle responses

- Difficulty returning to baseline after a scare

While not all of these signs are clinical, they are consistent, relatable indicators that animal professionals need to recognize and look for with the animals in their care.

Knowing When Medication Is the Right Choice

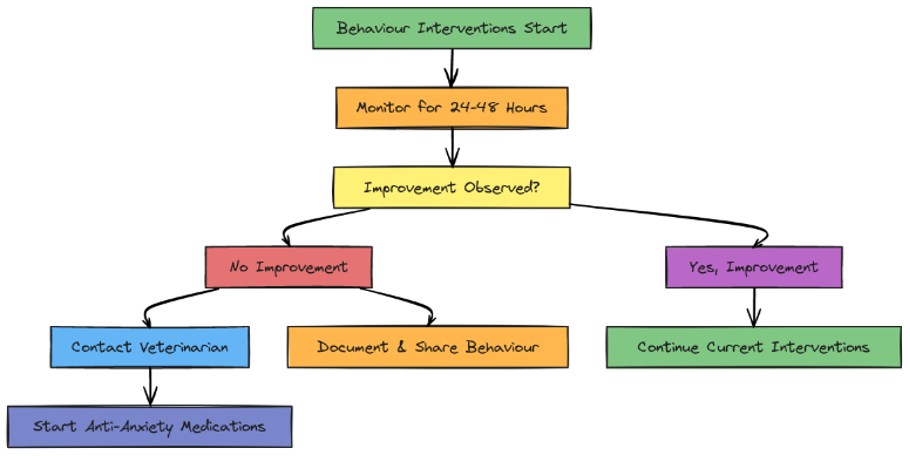

If enrichment, environment changes, or co-housing don’t lead to a noticeable improvement within 24 to 48 hours of being implemented, that’s usually a signal to consider anxiety-reducing medication. “You’ll usually know quite quickly if environmental interventions are working,” shared Dr. van Haaften. “And if they aren’t enough, don’t wait too long to explore other options.”

In emergency cases, such as self-harming, severely shut-down animals, or extreme escape attempts, medications should be started immediately. These animals aren’t in a place where training alone will help. In these situations, Dr. van Haaften sometimes starts at a higher dose and will adjust later, once the animal is more stable. It’s important to work with your vet on this.

Fast-Acting vs. Slow-Acting Medications—What Works Best for Animals in Shelters?

While SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) and other slow-acting medications are often used in private practice, shelter settings demand faster results. Fast-acting medications, like trazodone and gabapentin, offer quick relief that can help an animal feel better today, not weeks from now.

Dr. van Haaften warned that fast-acting medications need to be given more frequently, up to three times a day in some cases, and they carry the risk of side effects such as sedation. But when weighed against the urgency of reducing distress in a shelter, the benefits often outweigh the drawbacks. Plus, they allow staff to assess what progress is possible when anxiety is reduced.

Why Medications Matter—Supporting Training and Welfare

Medications aren’t just about short-term comfort for a shelter animal. Dr. van Haaften emphasized that when fear is reduced, behavior modification becomes more effective, and animals can build trusting relationships that can also help change behavior over time.

Dr. van Haaften referenced two studies in particular: one on gabapentin in fearful shelter cats from hoarding environments (Eagan et al., 2023) and another on Reconcile for dogs with separation anxiety (Landsberg et al., 2008). In both studies, animals receiving medication showed greater behavioral improvement over time compared to those given a placebo. They started to improve early and ended up in a better place overall.

As Dr. van Haaften put it, “Fear is the enemy when it comes to learning.”

How Long Should You Wait Before Starting Medications?

Dr. van Haaften recommended giving non-pharmaceutical behavioral interventions a window of 24 to 48 hours to prove their efficacy. If the animal does not show measurable improvement, either in body language or behavior, it may be time to consider medication.

Shelter life can be unpredictable, overstimulating, and overwhelming. For many animals, waiting too long to intervene medically means a risk of worsening welfare. In those cases, starting medication early can prevent further emotional harm.

Timing Medications With Training Sessions for Best Results

Did you know trazodone tends to peak about an hour after it’s given? Dr. van Haaften recommended syncing b-mod sessions with that peak window: “That first hour after the medication kicks in is often when you’ll see the most benefit from it in your training.”

For dogs with reactivity or anxiety, training is more productive when the medication is actively reducing stress. Know when the medication an animal is taking will be most effective and time your training session accordingly. Some shelters even use timed dispensers to automate dosing at times that align best with staff schedules.

The Power of Collaboration—Working With Veterinarians

Collaboration is essential. Veterinarians and other medical teams rely on shelter staff, volunteers, and trainers for details they might not observe in short appointments with an animal. At the same time, animal care teams need timely updates about medication starts, stops, or dosage changes.

Dr. van Haaften acknowledged that not all veterinarians receive the same training on animal body language or learning theory. Animal professionals can help bridge this gap by sharing observations in ways that are clinical, useful, and respectful.

Thorough recordkeeping, especially in shelters, is important. Honest communication and mutual respect also go a long way. Together, they are key to building a collaborative treatment approach.

Medications and Adoption—What You Need to Know

Can a dog on trazodone be adopted? Absolutely, but Dr. van Haaften quickly clarified that medications alone don’t make a dog adoptable. Behavior, history, the home environment, and the animal’s ability to cope without medications all matter.

“If they truly can’t function in a home without medication, we have to ask: are they adoptable at all?” noted Dr. van Haaften. “Medication doesn’t make an animal adoptable. It helps us see who they are underneath the stress.”

The goal isn’t just to place the animal, it’s to ensure they can thrive in their new home.

Bridging training and treatment to overcome anxiety in shelter animals takes teamwork, compassion, and the right tools, including behavior modification and, when needed, anxiety-reducing medication. With clear communication and understanding, we can help more animals succeed in shelters, rescues, and homes.

Transparency with adopters is key. That includes sharing whether the animal needs a plan to wean off the medication, and what behaviors to expect once the medication is tapered.

References

Eagan, B.H., van Haaften, K., and Protopopova, A. (2023). Daily gabapentin improved behavior modification progress and decreased stress in shelter cats from hoarding environments in a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 261(9): 1305–1315. DOI: 10.2460/javma.23.01.0044

Landsberg, G.M., Melese, P., Sherman, B.L., Neilson, J.C., Zimmerman, A., and Clarke, T.P. (2008). Effectiveness of fluoxetine chewable tablets in the treatment of canine separation anxiety. Journal of Veterinary Behavior 3(1): 12–19. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jveb.2007.09.001

Fear-Free Certified and a graduate of The Academy for Dog Trainers (CTC), Kim Monteith has over 20 years of experience in animal sheltering. She supports 32 BC SPCA centers with behavior and welfare cases, protocol development, and staff and volunteer training. She helped develop and continues to support AnimalKind, the BC SPCA’s science-based accreditation connecting the public with humane, professional trainers. Kim created systems for large-scale intakes and emergency pet shelters, and provides free training and support to unhoused pet guardians. She is a member of the Pet Professional Guild’s Shelter and Rescue Division.